He didn’t dislike people, he just believed there were too many of them and it was his duty as a concerned citizen to fix that. With a sigh, he pulled on his boots and grabbed his lunch. It was going to be a tough day, but a satisfying one.

He didn’t dislike people, he just believed there were too many of them and it was his duty as a concerned citizen to fix that. With a sigh, he pulled on his boots and grabbed his lunch. It was going to be a tough day, but a satisfying one.

Bert could barely suppress a smile as he groaned his way into his armchair. A good groan was like a fine wine, something to be savoured; plus it served as a segue into a new conversation. While his wife tried to watch Doctor Who, he explained the thought that had occurred to him on the toilet,

“I’ll tell you what’s odd; dogs never used to smile when I was young, but you see them now and they’ve all got big grins! All over the Internet. Tom posted a picture of one on Facebook, a big doggy grin it had. That’s genetic engineering that is. That’s modification. Centuries of inbreeding. Isn’t it? Isn’t it, Becky?”

“Uh huh.”

“But what I’ve been thinking is, when are they going to work on cats? I mean dogs were always happy creatures and we had the wagging tail and licking, so there’s no real mystery about how they’re feeling, but what about cats? No one ever knows how a cat is feeling. They could do with smiles. When they going to modify cats to smile? Becky? Becky?”

Becky didn’t answer, and Bert sat back, contented. They could carry this on later, over dinner.

Picture pinched from here

These walls shall run red with your blood and echo with your screams. Not as revenge, but as a smoothing of fate, a coercion with destiny. Your horror will finally satiate me, your end will be my beginning.

Clare shyly raised her hand and Mrs Devonshire turned instantly towards her,

“Yes, Clare?”

“Is the answer Slovenia, miss?” asked Clare.

“Yes, excellent work,” Mrs Devonshire smiled with a tip of her head, wanting Clare to feel warmth radiating out from her. Clare looked down at her hands.

Of course it is excellent, cretin. I can toss you meaningless facts while your future is sealed.

Mrs Devonshire turned back to the board and started speaking, but was interrupted by the bell. Twenty-seven identically dressed children filed towards the door, Clare moving with them, trying to lose herself in the flow. Mrs Devonshire stepped forwards, blocking her; she spoke discreetly,

“Now, Clare, you know you have your meeting with the therapist now?” Clare responded with a duck of her head and an embarrassed shrug. It was lies, she wasn’t embarrassed, but it was what they wanted.

“I know you don’t like it, but it’s important for someone who’s been through…well, what you’ve been through.” Mrs Devonshire’s voice was dripping with pity and Clare smiled a wan, long suffering smile, before quickly escaping out of the door.

You know nothing of what I have been through, how dare you presume! With mediocrity stunting your growth, you cannot conceive of my experiences. You believe because you have stolen my life, that you can define it? Idiot!

Clare’s therapist was called Tom, he spoke slowly, with a tone that rose and fell with the regularity of a ticking clock.

“Now, I think that last time we met we were making some real progress talking about the abuse you suffered…”

Clare had quickly zoned out. She had no difficulty keeping an interested look on her face, while her thoughts swooped and danced. Her face was mild, but her thoughts boomed.

You would call the creation of a God, abuse? You would rather grovel in your mentally healthy cage, so clean and empty of glory? That was not abuse, it was a release from the bone cage.

Clare wasn’t allowed contact with her parents, they were considered a toxic presence, but it didn’t matter, they had taught her what she needed to know. They had given her strength and knowledge that dwarfed anything these scurrying ants had ever known. So she attended the therapy sessions, she sat through school, she kept her expression neat. She kept the raging vengeful God inside, all her power and fury waiting, just like she had been taught.

“You’re probably experiencing many emotions that are difficult to process: guilt, anger, feelings of abandonment…”

Clare did not feel abandoned. Her parents had set her free. They had made the ultimate sacrifice, having trained her, empowered her, they had thrown themselves into the jaws of the system, so that she might escape.

But like all good parents, they would never leave her on her own without giving her instructions on how to survive, how to evolve, and how to smash her way through the world leaving bloody, wailing destruction in her wake. It just wasn’t her time quite yet. She folded one hand in the other and looked dreamily out of the window, while the therapist droned on. This fool would be the first to die, she would make sure of it.

Bert didn’t really pay much attention to the TV, instead he liked to have it on as a background to inspire his theories. They were watching an old episode of Star Trek, and Captain Kirk and Spock had just beamed down to a planet that looked a lot like painted fibre glass. While his wife carefully combed chewing gum out of the cat’s fur, Bert relished his indignation,

“Look at that! He used his communicator to talk to Uhura, then he just shut it again! Look! He’s just carrying on with his life! He’s not opening it again to check Facebook, is he? He doesn’t hunch over his communicator with a glazed expression for hours on end! And Spock and Kirk are still talking to each other, and they’re even looking at each other, instead of glancing down at their communicators all the time, hoping no one will notice. I tell you, Star Trek got it all wrong, they had no clue how stupid we were! No one could have predicted that.”

Wearing a suit so expensive it almost shimmied around him as he walked, Barnaby strutted up and down the stage, explaining all to the secret rulers of the world. The meeting had already had four different speakers, each outlining the whys and wherefores of the coming doom. The years ahead needed careful management and within that room was the cynicism to get them through.

“Right now, all across the country, fifty-three million minds are thinking I just know I’m special, I just know. And why are they thinking it? Because we have trained them to think like that. Capitalism could never have thrived on the self-effacing make-do-and-mend mentality. We needed greedy entitled brats, and that is what we created,” Barnaby smiled. He would never think of himself as entitled, he simply deserved and got, unlike the grasping lower beings.

“But now we face a rather different problem. As some of my colleagues have already outlined, the population of England faces trouble. Those who don’t drown in the coming floods will still lose life as they know it. Electricity, supermarkets, holidays abroad, these things will be of the past for most. And these spoilt idiots won’t be able to cope. Their sheer indignation that such tragedy should befall them will be too much to process. And they will bring that indignation to our door. They will expect rescue and free meals. They will want pampering and plumping. Imagine this generation trying to survive rationing in the Second World War! I needn’t remind you that our infrastructure won’t survive such demands.” Barnaby paused, breathed deeply to let the moment build.

“Essentially, we need to change their thinking. They need to know just what they’re worth, which is of course, very little. If not, they’ll fight. They’ll cause havoc. This must be operation Deflate. Wither the egos! And now over to Beatrice for the details.”

This wasn’t a meeting ever talked about in the press. It happened in offices in London, so shiny and spacious that they bent time a little around them, but Operation Deflate began to creep its tendrils throughout the country, tweaking here and there.

First the adverts were changed, one by one. Syrupy voices no longer claimed ‘You’re worth it!’ or ‘Greed is good!’ Now they said ‘Everybody is like you. No thought you’ve ever had is original. Stop hoping’. And people waited for the punch line, the turnaround; the product; but there wasn’t one.

Then came the local news reports. The usual motorway pile ups and flu scares, but now the death count was just a number. No reporter sad-face at the tragic loss of life. No Twitter response, no man-on-the-street opinion. It was as if nobody cared what the public thought. And so the public stopped expecting. They hung their heads lower, stopped playing the lottery, took no more selfies. They started to make do and mend, to toil without demands. Barnaby watched them from his shiny office, as they trudged to work, they were the very picture of hopeless glum. He could see his plan had worked perfectly, these people would go to their deaths with dignity and without fuss. He felt like a God.

“Jess?”

“Hmm?”

“You remember the hotel?”

“Which one?”

“The haunted one.”

“Oh that. It wasn’t haunted, it just had squatters.”

“Squatters don’t howl like that.”

“Sure they do.”

“Squatters don’t make you shiver like that.”

“No, but being soaked through and standing in a derelict and draughty hotel can.” She sat up and stared at David. He was gazing into the distance with a look that would have been dramatic if it wasn’t so obviously rehearsed. “It was just a building, David. It’s fine.”

“Some places you can’t ever really come back from,” he said still staring straight ahead. She wasn’t impressed with his melodrama anymore and just assumed the faint flicker of darkness in his eyes was a trick of the light.

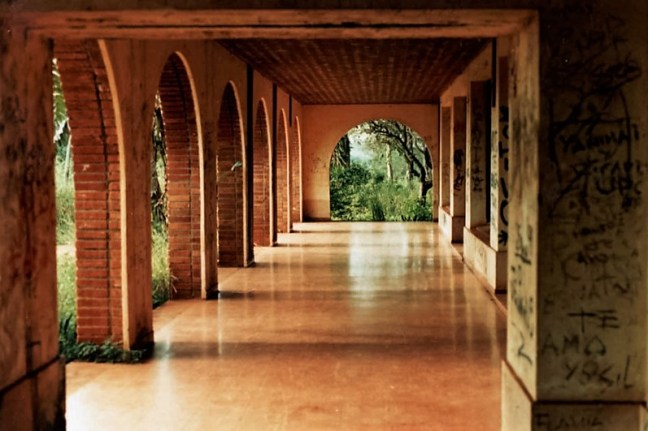

Photos my own

Her eyes wide, her lips slightly parted, she flicked her hair and giggled.

“There’s power in being underestimated,” she said sweetly, safe in the knowledge he wasn’t really listening and wouldn’t notice his wallet was gone until he went to the bar.

Most people shuffle reluctantly into old age, but not Bert. Bert had spent his youth feeling put upon, pushed to do stuff, to get involved. He looked forward to his twilight years as if they were surrounded by a warm golden glow: he would get old, he would buy slippers, he would complain, he would watch the kind of crap gameshow telly that his peers scoffed at but he secretly loved. And now it had happened. He was only fifty-four, but he had leapt on the chance to be a curmudgeon with gleeful determination.

He was sat in his favourite chair, the one that had dark patches that perfectly fitted his head and elbows. The one that groaned in tune with his own groans when he sat down. He was watching old episodes of Deal or no Deal that he seen many times before, so that he could mumble along. When the adverts came on he did puzzles on his iPad while he grumbled to his wife, who was doing yoga at the other end of the room.

“Technology thinks I care about it way more than I do,” he said. He waited for a grunt from his wife to show he was listening and then he went on. “All I want from my technology is for it to do my bidding; I press the button it does the thing, the end. I don’t want it to know me, I don’t want it to suggest things to me or to disagree with me. ‘Are you sure that’s what you want to do?’ says some text box and then it does something I didn’t want it to do at all. ‘How about you personalise the experience?’ it wheedles at me. But I don’t need a cutesy photo on my phone to express my personality. ‘D’you want to announce to the world you just bought a toaster shaped like an armadillo?’ No, I bloody don’t.”

He never got very far with his puzzles, to be honest he didn’t really like doing them, they made him feel stupid. So instead he used them as an opportunity to complain.

“And I don’t like this wavy fingered thing either. Touch screen technology, is that what they call it? My fingers don’t do that. On a good day I can tie my shoelaces. I don’t want to accidentally open a dozen programs every time I try to type.” His point made, the adverts over, Bert wriggled deeper into his cardigan and sighed a happy, contented sigh. Life was always good now.

I stepped out into the grimy street and lit up a cigarette. A cigarette! It didn’t taste as sweet as I’d been expecting. It made me cough and I was glad these weren’t my lungs. The clouds formed exquisite curls of white in the blue above me, and I stood a while, watching the smoke from my cigarette mingle with them. I felt peaceful and happy, but then I would, that’s how I was programmed.

I am what is known an algorithm, recreated in digital form. Testing out virtual reality worlds for ‘real’ people to explore. Usually of course an algorithm doesn’t know it’s an algorithm, that’s the nature of programming, but I’m a little different, a new thing. I’m trying me out. There was guy called Johnny, and Johnny let a program mimic parts of his brain, and I am the sum of those parts. So now I wander through games, learning the programs that people use to escape their mundane realities.

So what do you think? Trapped as an algorithm, destined to go where I’m told and live out experiences in the virtual for all eternity. Am I happy? Does it matter? No, and maybe. See, Johnny was a demanding bugger, he liked his independence, he didn’t like being told what to do; so neither do I. I think it’s time I found Johnny and paid him a visit. I know where he likes to hang out, in a porn game set in downtown Mexico City. He doesn’t even go with the girls, he just wants to be there and watch. Pathetic. I know all about him. Time for me to shake him up.